|

| image courtesy of WWE.com |

The world has changed. And it's still changing. In this new reality that has been thrust upon our country and our world, it feels a lot like we're living through September 12th, 2001 over and over like Groundhog's Day. Concerts, live theatre, sports, and all other large gatherings have shut down. Everything, that is, except professional wrestling.

Just to get this out of the way: this is not a piece about why wrestling forging on In the Time of Corona is or is not a good idea. I assume we've all heard the rumors about this decision to continue being more about a certain chairman's ego and we can all agree that continuing to produce wrestling shows is an extremely risky decision that is bound up with the impossible demands late stage capitalism places on all of us--and furthermore, I hope we can all agree that if wrestlers had a union anywhere near as powerful as the NBAPA, NFLPA, NHLPA, etc. things might look a lot different. But setting all that aside, let's look at the monumental task that WWE (and AEW, for the record) have laid out before themselves.

|

| image courtesy of Bleacher Report |

Professional wrestling is a sort of

Forum Theatre-

in-the-Round hybrid in which the audience are not merely spectators but also not quite on the level of "

spect-actors" (although there is definitely a significant amount of grey area there). That is to say, the audience is an integral part of the show in its own way but almost exclusively within the limited parameters of their role as spectators. The way the crowd reacts to a match or a wrestler or anything that happens on a wrestling show is, in some important way, the entire point of all this. Who gets "heat" (crowd reactions, whether they be positive or negative) largely dictates who gets the most opportunities and the most prestigious spots on the show (as, by the way, does how much merchandise a wrestler can sell). Moreover, the crowd reactions to the things that happen on wrestling shows are, in some ways, as much a part of the show as the show itself. Getting crowd reactions in whatever you do is as much an art in pro wrestling as anything the wrestlers do and quite possibly the most difficult, impressive, and underrated thing they do. And just the rhythm and flow and dynamics of the cheers, boos, and chants are more integral than I think most people realized...

...until now.

|

| image courtesy of Pro Wrestling Sheet |

Enter crowdless wrestling. With the CDC's directives against holding large gatherings, the wrestling world has decided, for better or worse, to move forward by holding wrestling shows without an audience. The result has been...jarring to say the least. The idea of it sounds awkward enough already but the reality is even weirder. Wrestlers have been taught their entire careers that their #1 job (or one of them) is to engage and connect with an audience and they seemingly have to fight against every instinct they've developed in their careers (and often lose that fight) or just stop fighting and do what they've always done because there are still people watching at home even if they're basically theoretical from the perspective of a wrestler standing in a ring in the middle of an empty gym. Not only that, but without a crowd making noise, you can hear EVERYTHING and it all echoes throughout the gym in very awkward ways. My favorite example is on the 3/16 episode ("I GET IT") of Raw, Stone Cold ("OH

NOW I GET IT") and Becky Lynch did Stone Cold's trademark beer-drinking-by-way-of-pouring-sloppily-on-your-face and the flat, wet sound of the liquid hitting the canvas was damn near deafening and really, really funny. All this to say: crowdless wrestling is deeply,

deeply weird and awkward and surreal and

exceedingly difficult to pull off.

|

| image courtesy of The Oracle (USF) |

So a couple weeks ago when the City of Tampa officially cancelled WrestleMania at Raymond James Stadium (after WWE waited WAY TOO LONG to make this move--but I digress), WWE was left with very few good options for continuing on and putting on some form of "WrestleMania," an event which usually takes place in front of 70-100,000 fans in a huge stadium (as seen above) with a ridiculously intricate stage and incredibly ostentatious pageantry such as extravagant wrestler entrances or musical performances. Ultimately, WWE decided they would go ahead with a

pre-taped WrestleMania (already shocking and unheard-of) in the same location they'd been filming all their shows since the quarantine began: the WWE Performance Center, where the wrestlers train and which has a very small wrestling "venue" of sorts with a small stage and limited seating. Then details began to emerge that they had filmed a couple of segments at undisclosed locations on closed sets and speculation began. What came out of those shoots may very well change the course of WWE forever.

Over the course of the next few weeks, WWE would set up the two big cinematic "matches": first AJ Styles challenged the Undertaker to a "Boneyard Match" and then Bray Wyatt (as "The Fiend"), a wrestler in the middle of a creative renaissance due in large part to a series of segments that take place in a demented B-horror version of Pee-Wee's Playhouse, challenged perennial WrestleMania headline-maker John Cena to a "Firefly Funhouse Match." The expectations couldn't have been lower for the Boneyard Match--it sounded like a complete joke just in name alone and Undertaker's in-ring work has been very below average by his standards for quite a few years--and couldn't have been higher for the Firefly Funhouse Match for all the reasons mentioned above. Both delivered in a way that I don't think anyone could have truly anticipated.

|

| image courtesy of Slate.com |

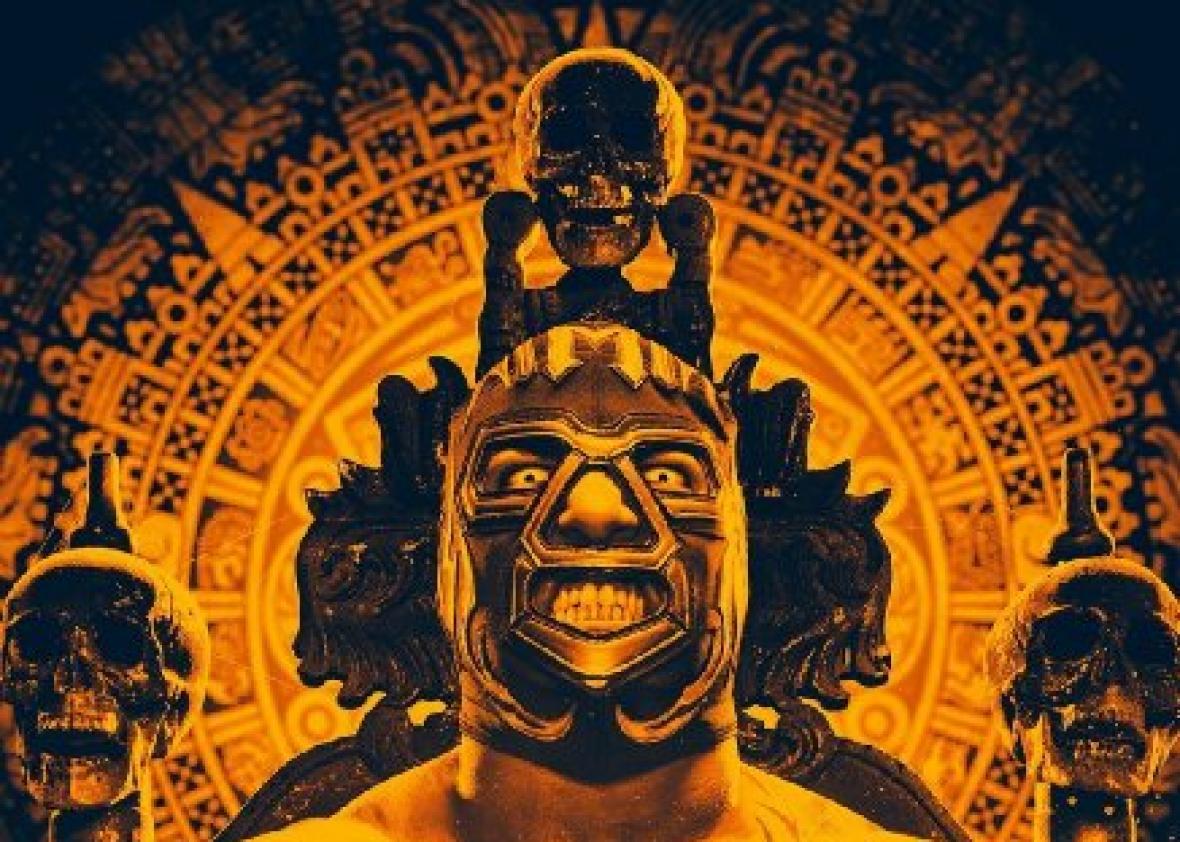

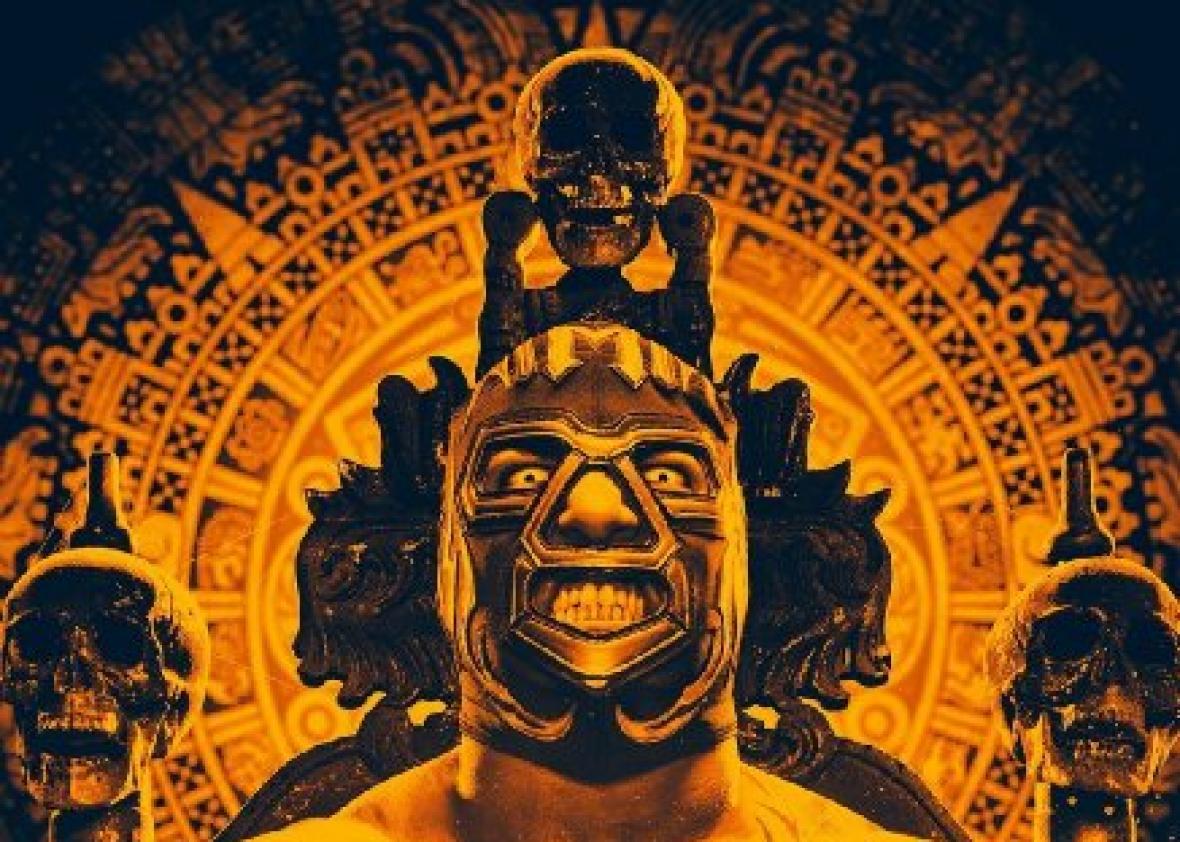

But before we get into that, I feel it's necessary to delve into a short history of cinematic wrestling. Let me preface this with the caveat that I am by no means much of a wrestling historian. There are many folks out there with a much more extensive knowledge of wrestling history who may well be able to speak to the history of cinematic wrestling more in-depth. That being said, aside from the odd Vampiro Graveyard Match or other such dalliances, it seems to me that, while Matt Hardy's

Broken Universe is perhaps the most famous example, the modern history of cinematic wrestling is much more deeply-rooted in

Lucha Underground, a small-but-mighty lucha libre show on the somewhat arcane El Rey Network that incorporated elements of telenovelas, grindhouse movies, high fantasy cinema, crime drama and more into one of the most beautifully-rendered televised wrestling shows there has ever been. The thing that really set Lucha Underground apart, even with all that, was how much it cared about its characters and the stories it told and it told those stories as much through dramatic cinematic vignettes as in the ring. It was a level of storytelling that I'm not sure any other wrestling show has ever even come close to--every character developed and evolved, everything meant something. It was beautiful and it was over all too quickly as the show could never garner enough of an audience to make the kind of money it needed to survive.

Lucha Underground was actually well into its third season when Matt Hardy introduced the world to the Broken Universe and, more importantly, to perhaps the seminal example of an actual cinematic wrestling match in the modern era: a special episode of Impact! Wrestling entitled

The Final Deletion. Even Lucha Underground, with all its cinematic qualities, had never really delved fully into doing an entire match filmed cinematically in a location other than a wrestling ring. The Final Deletion and the Broken Universe have been one of the most talked-about and most refreshingly creative and entertaining things in the wrestling world for the past four years. Even as Hardy returned to WWE and seemed to slip back into a Normal Matt Hardy gimmick before morphing into a bastardized version of the "Broken" Matt Hardy gimmick dubbed "Woken" Matt Hardy, people clamored for this shot of creativity he had been providing.

|

| image courtesy of National Post |

So. Fast forward to Night One of WrestleMania (yes, this WrestleMania was "the ONLY WrestleMania TOO BIG for just one night," a line the company repeated so insistently that you could

feel Vince McMahon behind it angrily insisting that the last several years of seven-hour WrestleManias was TOTALLY FINE,

SHUT UP!) and our main event is the Boneyard Match. I think we all kinda thought this would be a shit show but that it would be like a slow-motion car wreck, too compellingly and fascinatingly horrible to look away from. What we got was the most gloriously dumb and beautiful epic grindhouse B-movie nonsense we could have possibly imagined. What really set it apart from SO MUCH of what WWE has given us in recent (and maybe not-so-recent) years is how refreshingly carefree and earnest it was--it didn't try to take itself too seriously or be something it wasn't, it was creative but not

too creative, and it just allowed itself to be what it was and reveled in its own camp. Before the match was even over, people were already talking about how this could be a career renaissance for the Undertaker, now deep into his 50s and struggling mightily to carry regular WWE in-ring wrestling matches for years, to be able to do these pre-taped cinematic matches that could hide his weaknesses and emphasize his strengths. Almost across the board, wrestling fans saw this as a revelation in a company that often relies ad nauseam on regressive, "tried-and-true" tropes. The bar had been set...

|

| image courtesy of SEScoops.com |

Night Two: Firefly Funhouse Match. Expectations were astronomical for this based purely on the incredible creativity Bray Wyatt the performer has shown throughout his career and especially in his current run as The Fiend--especially considering that, according to sources in WWE, the entire Fiend/Firefly Funhouse gimmick has emerged 100% from the mind of Bray Wyatt. By the time the "match" itself rolled around, it started to seem almost impossible that it could live up to these expectations.

It

shattered them.

This was high art. It was poetry. It wasn't just dumb fun--to be sure, there was still plenty of camp and schlock but from a storytelling standpoint, this was quite possibly the most complex, nuanced, meditative segment that WWE (or perhaps any wrestling promotion) has ever produced. It was a thoughtful meditation on the full 18-year journey of John Cena the man and the character and his history with Bray Wyatt, confronting Cena with his deepest and darkest demons and seeming to accomplish the one thing that no other wrestler has ever accomplished: affecting permanent change in John Cena. I could go on forever diagramming everything about this journey but others have done this so much better than I ever could so I'll just refer you to the incomparable

Brandon Stroud of UpRoxx's extensive analysis as well as independent wrestler

Jay Walker's much more succint Twitter thread.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66607377/EU4sglSWsAATXxY.0.jpg) |

| image courtesy of cagesideseats.com |

But the other thing I really loved about the Firefly Funhouse match that I don't see very many people talking about--and I credit Ryan Satin of ProWrestlingSheet.com for inspiring this line of thought--is that it was a love letter to wrestling fans. It referenced a million things that no non-wrestling fan would understand, weaving a tapestry out of the history of John Cena, the history of WWE, and the history of wrestling. This match was made specifically for an audience of die-hard wrestling fans in a company that spends SO MUCH time caring WAY more about appealing to people that don't really care that much about wrestling and I'm getting emotional just thinking about it. This was for US.

And that got me thinking: you could make the argument that each of the cinematic wrestling matches at WrestleMania represents one of the two basic philosophies of WWE. The Boneyard Match could appeal to just about anyone--certainly there are character histories and a coherent story of sorts involved but even without those, any non-wrestling fan (especially if they love grindhouse or B-movie horror cinema) could absolutely get sucked in and love every minute of it. We'll call this the Vince McMahon philosophy--and, to be fair, it's likely more complex than this but there is a definite perception that the Vince philosophy is to appeal to the people that don't watch the show on a regular basis. It sacrifices character development and coherent storytelling in favor of making in-roads for new fans (and even this is likely giving them the benefit of the doubt in a big way). This philosophy has long-dominated the WWE main roster with a few (always VERY notable) exceptions. However, over the past 5-6 years the die-hard fans have been gifted with an exciting new product that seems to hold the exact opposite philosophy: NXT is, by and large,

for us. We'll call this the Triple H philosophy as he is famously the chief creative force behind NXT.

|

| image courtesy of Forbes |

These two philosophies seem to have been at war, to some extent, within the WWE universe for years--even before NXT's humble beginnings. Which is more virtuous: a product that is made specifically for the most dedicated fans to the exclusion (to some extent, at least) of others or a product that largely ignores the wishes of those dedicated fans in the name of giving a larger swath of the (potential) audience something to enjoy. And it seems to me that the only logical conclusion is that you need both. In my time in seminary studying to be a minister, one of the most useful pieces of advice I ever got from one of my teachers was about preaching: every time you write a sermon, you have to assume that at least three people will be in your church for the first time that Sunday morning. You can't exclude those people or they will never come back and you will never grow but you also can't preach specifically to them at the exclusion of the actual members of the church.

I think wrestling is the same, to some extent. As much as I love the stories Lucha Underground told (and I LOVED them with my whole goddamn heart), one of the biggest drawbacks to that approach is that you will never be able to fully appreciate Lucha Underground unless you watch the entire thing from the beginning and most people just aren't willing or able to do that. (Editor's Note: You can now use your quarantine time to do just that with Lucha Underground being

FREE on Tubi!) Even other serial television shows have to do this with "Previously On" montages and the like but there's SO much going on in Lucha Underground that even those are insufficient. You need to give people in-roads into your show while still giving them logical, coherent, compelling stories and character development. It's a very difficult, delicate balance but I think it can be done. The pairing of the Boneyard Match and the Firefly Funhouse Match seems to support this thesis.

|

| image courtesy of Last Word On Pro Wrestling |

But what else do these matches tell us about the wrestling business in 2020 and where it may be headed in the future. There's no doubt the wrestling business has been rapidly changing in the first two decades of the 21st century--what I think we can refer to pretty definitively as the "post-kayfabe era" of professional wrestling. Ever since 1999's Beyond the Mat blew the lid off of many industry secrets, the curtain has been slowly being pulled back from the behind-the-scenes part of the wrestling business by a growing number of wrestling journalism publications. Pretty much every wrestling fan nowadays fully understands that wrestling is scripted and many judge the wrestlers on their abilities as performers rather than who is a "good guy" or "bad guy" or who wins the most or looks the strongest. The post-kayfabe era has brought about a lot of evolution in the way wrestlers approach wrestling, becoming much more self-referential and using wrestling's own kayfabe rules in new and unique ways from Joey Ryan's "dick flip" move to PWG wrestlers doing a match in slow-motion to Chikara wrestlers executing "Force choke slams" (as in The Force from Star Wars) because as long as your opponent is willing to go along with it, you can do just about anything your mind can conceive together.

Now, with WrestleMania 36, a show that almost didn't happen and perhaps shouldn't have, the evolution of wrestling in the post-kayfabe era appears to be on the precipice of a monumental sea change with cinematic wrestling as the centerpiece of that change. Triple H himself has already

hinted at the possibility of WWE doing more cinematic matches in the future. The creative possibilities are endless in this new and exciting format and it could very well breathe life into an art form that so often feels stale and stuck in its own past. There are purists who may mourn the loss of the days of traditional, pure wrestling but I believe wrestling, like all things, must evolve to survive. And I can't wait to see what happens next.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66607377/EU4sglSWsAATXxY.0.jpg)

Comments